Lavongai is a place where an anthropologist recently decided to leave after a couple of weeks of exploratory fieldwork because she said they had lost their culture. It is a place where the expatriate missionaries say the people have lost their culture. It is a place where many of the inhabitants themselves say they have lost their culture. Admittedly, there is a lot to be said for the case that the Lavongais have lost their culture. In the most 'obvious' sense of culture, as many of the Lavongais themselves use it, meaning music, dance and decoration, there is indeed little to be witnessed. There are few occasions where a call is made on these fanciful displays of 'culture' and much of the required knowledge is either lost or only home to a handful. Another aspect of culture, kastam, which in Lavongai is at its strongest in connection with funerals, is also subject to considerable strain. Many 'customary laws' are discarded or broken, corners are often cut as the burdens of kastam are viewed to weigh too heavily on a people exposed to a world involving money. Values, taboos and beliefs are also subject to revision in a cost/benefit evaluation in a changing society. In her thesis Billings argues: "it may be that times never were as they should have been. Institutionalized forms may well have been talked about as standards of excellence that came from the old days, rather than standard operating procedures". This is arguably true for all societies at all times, however there is a case to be made that this rings very true to Lavongai society, because of the somewhat 'laissez-faire' attitude of the Lavongais. Regardless of the fact if Lavongais were strong adherents of their kastam or not, the main cause for its rapid 'disappearance' was Christianity. It's hard to say why Christianity was so successful in wiping out many of the old ways so quickly in Lavongai, but it may well be that the Lavongais weren't too content with the old ways. The fact that they are such good Christians is one of the things Lavongais pride themselves with the most. In a sense they also consider Lavongai to be God's country. So is Lavongai culture lost? It is not. On the one hand there is the conscious revival of culture. It's main aim is to re-attain a sense of unity and pride and to occupy the youth, mainly referring to an ever-growing group of young men who have no money-making opportunities and are want to cause 'humbug' in their boredom and frustration. On the other hand one can see culture as the lived reality in which people exist, meaning if there are people there is culture. And what a culture it is! An exciting mix of black magic, poison, sea pirates, cannibal heritage, greed, business, competition, political intrigue, jealousy, land disputes, shame, and dreams all deeply rooted in the Papua New Guinea of today. Apart from fishing and gardening the lives of contemporary Lavongais revolve around frequent trips to Kavieng, a constant scavenging for petrol money, the skilful operating of banana boats, Christianity, politics, the Ling-Stuckey Foundation, beetle nut, kastam, ancestors, clan membership, and remittances. It is no longer possible to view Lavongai in isolation. Lavongai is entangled in processes of globalisation and localisation. The doings of a nationally disgraced expatriate may cause clan disputes in Lavongai or an escaped convict from a Port Moresby prison may cause unrest in the area. Or the other way around, the dealings of a son of Lavongai may cause half the working nation to lose half their life savings. On a global scale, Papua New Guinea is very much the periphery, and thus of course Lavongai more so still. The fluctuation of world market prices for copra or cocoa indeed affect the Lavongais, but it seems fair to say that the island community is far more touched by matters at a national level. Nevertheless the outside world is felt, mostly flowing in through foreign media and people. The flow out is all but non-existent, save perhaps for some exotic imagery of cultists and an island paradise. Papua New Guinea is still very much bullied by the IMF, the Worldbank, and most of all by Australia. Australian dominance is felt, even at a local level. The order of things is made very clear to the Lavongais in Kavieng, which is owned by expatriates (mostly Chinese and Australians). The atmosphere is still awkwardly colonial and there is a very high barrier for a Lavongai to ever get his foot in the door. Sadly there is also a belief in black inferiority. Based on time and observations, the white man is seen to be superior in thought, action and discipline. To make it sadder still this belief is substantiated by reference to the Bible: the curse of Ham or to be more exact his son. Genesis 9:25 "Cursed be Canaan! The lowest of slaves will be he to his brothers." However the Lavongais consider themselves very lucky, not like the unfortunate Africans, with whom they feel a certain similarity. Lucky because they themselves have a beautiful country, rich with resources and ample food. The rhetoric of 'PNG and the richness of its resources' together with the question of why development is lacking is one used at national, provincial and local level. Lavongais consider themselves political beings, and conversations between men are often of a political nature. They are very lucid and realise that everything about Papua New Guinean living is politicised, from education to development. One does not obtain monies through the laws of the nation and the rights of the citizens. Now the unwritten regulations regarding the acquisition of funds lie in keeping the granter in place or up a notch on the political ladder. And in such a world an anthropologist too becomes a political commodity, to be given by one 'benefactor' and taken away by another. This is perhaps in many ways a far more interesting and challenging time, where modern elements have been incorporated and old ways have been discarded, retained, adapted, revived and even 'augmented'. Today in Ungalik the young men with too much time on their hands are gratuitously experimenting with black magic, causing a resurgence of this practice at a rate that surpasses if not the time of the ancestors definitely of the past couple of decades. This is a time where the coastal Lavongais still have suspicions of cannibalism among the inland people and a time where the coming of a supermarket is the cause for much commotion. A man from Buka who lives at Mansava secretly admitted that he found it all quite laughable, because where he is from they have had things like supermarkets for many years now. Lavongais are struggling to deal with these times in terms of 'development' and their identity. The Lavongais consider themselves smarter than the rest, but there is a conflict. It's one thing being smarter than the rest, but you need something to show for it. The Lavongais are painfully conscious of the fact that the Tolais, the Bougainvillians, the Sepiks and the Highlanders are far more enterprising than themselves and are thus admittedly regarded as enjoying a higher standard of living (pertaining to such things as money, permanent houses, roads, and health care). The main support for their assertion of their great intelligence is based on the fact that there are so many people from Lavongai occupying top, mainly government, positions. In the past, the time of toying with the Australians during the 'Johnson Cult' period, seems to have also been a testimony to their argument, however this sword cuts two ways, because for many it is also considered an embarrassing history which undermines their claim to intelligence. The anxiety they feel today stems from the knowledge that their heyday is over. They did not manage to make the most of their advantage. The cream of Lavongai was mainly educated during the 60's when they were blessed with a number of dedicated expatriate teachers. Today no such advantage exists. The standard of schooling in Lavongai has decreased and there has been a sharp increase in population. The opportunities for the youth seem far more limited. Many also have no ambition to leave the island, because through the years a consensus has been reached that 'city life' is not enviable. Almost all the Lavongais who have moved away from the island to work in an urban centre wish to return to their home at some time. More often sooner than later. Many don't seem to enjoy the work experience very much at all, and the majority do not feel that the benefits outweigh the costs, especially now with the cost of living in Papua New Guinea being so high. The main gripe that all Lavongais seem to have with city life is that everything costs money, and this causes them great stress. They almost always refer to the fact that at home they can walk into the garden or throw a line into the sea and they will have food. Maclean writes that "Some deal with the situation through a radical withdrawal into autonomy; they self-consciously adopt the identity of bus kanaka". This is arguably a bit too strongly phrased, but in the case of Lavongai there does seem to be a far more hesitant attitude towards the leap into (Western) freedom, which is linked to a disappointment of what has been accomplished. The 'viability' of hiding in autonomy is strengthened by the relative geographical isolation of the island, which is at the same time one of the factors that have contributed to Lavongai's lagging 'development'. _________

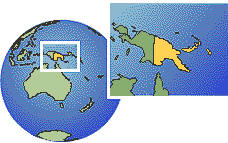

1Lavongai, also known as New Hanover, is an island off the coast of New Ireland, Papua New Guinea.

|